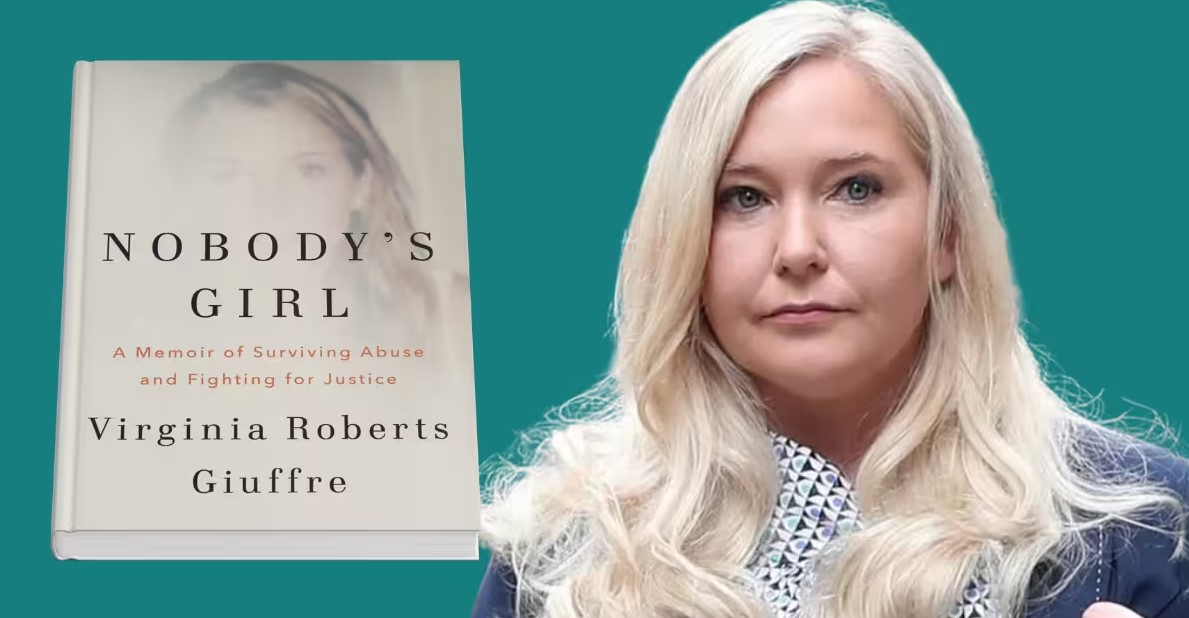

Nobody’s Girl is the life-sized account of how a Florida teenager with a history of abuse was recruited by Ghislaine Maxwell outside the Mar-a-Lago spa and drawn into Jeffrey Epstein’s network through a “massage” pretext; how grooming standardized ritual and obedience while adults normalized criminality; how she left, married, raised children in Australia, and then reentered the public square after 2018 with lawyers (notably Sigrid McCawley) and survivor allies.

How depositions, media battles, Maxwell’s trial, and the Prince Andrew Newsnight fiasco culminated in a civil settlement and a donation to her victims’ nonprofit; and how the book’s true endgame is law reform—eliminating statutes of limitations, launching SOAR, and teaching the public to detect trafficking—while acknowledging the nonlinearity of healing and the cost of advocacy.

The collaborator’s note confirms extensive corroboration and, after Giuffre’s death, records her explicit instruction to publish the book “regardless of my circumstances,” preserving her purpose: “awareness is growing,” and it must grow faster.

If you’ve ever wondered how a child is groomed into silence and how a woman claws back her voice, Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice shows the machinery—and the antidote.

Virginia Roberts Giuffre with a photograph of herself in April 2025, as a teenager

This is the posthumous, unflinching account of Virginia Roberts Giuffre—how childhood abuse primed her for Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell’s trafficking network, how she escaped, and how she turned her pain into sustained legal and legislative advocacy so other survivors can be heard.

The memoir’s collaborator explains a rigorous corroboration process—thousands of pages of public court filings, sworn depositions, and Epstein’s flight logs—plus interviews with family members and attorneys to vet events and timelines. On the broader problem, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children documented a 106% surge in CyberTipline reports at the pandemic’s onset, confirming the systemic risk Giuffre describes.

Investigative journalism (e.g., Julie K. Brown’s Perversion of Justice) exposed long-standing institutional failures around Epstein, contextualizing Giuffre’s case.

Best for: readers seeking a survivor-led, meticulously sourced narrative; students of law, journalism, gender studies; advocates working on statute-of-limitations reform; book clubs willing to sit with discomfort.

Not for: readers looking for gossip, new “name-and-shame” revelations, or tidy closure; the book centers systems, grooming, recovery, and reform, not sensationalism.

📚 Read Also: Top 10 Economics Books That Changed the World

1. Introduction

Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice by Virginia Roberts Giuffre, completed with journalist Amy Wallace, was published posthumously in 2025 (Knopf/Penguin Random House).

The book is narrative nonfiction—part survival memoir, part public-interest chronicle of law, media, and advocacy—and it documents a life shaped first by household abuse and then by the predation of Epstein and Maxwell. Giuffre writes to change policy as much as to record trauma; she argues for eliminating civil and criminal statute-of-limitations barriers that silence victims for decades. “My point: while Jeffrey Epstein is dead and gone, there are many others…still committing the same kinds of crimes,” she writes, insisting survivors “will always be stronger when we work together.”

The central thesis is that grooming, coercion, and complicity are engineered—then weaponized to discredit victims—so reform must be systemic, not individual. The memoir exists to bear witness and to drive legal change, anchored in corroborated records.

Crucially, the collaborator describes corroboration with family interviews, fact-checking, and court materials—“thousands of pages” that ground the narrative in verifiable evidence.

Publication arrives amid renewed scrutiny of institutions, from media to monarchy, that failed to protect children and enabled impunity for elites. (

Giuffre frames human trafficking as “particularly venal,” underreported, domestic—not just “elsewhere”—and exacerbated by the internet’s reach. She cites NCMEC-tracked surges during COVID and the scarcity of dedicated law-enforcement units (only 4% in the U.S.), to explain why many victims flee multiple times before escape. Public-interest journalism amplified this blind spot—Julie K. Brown’s 2018 Miami Herald series helped revive the Epstein cases—while the 2019 BBC Newsnight interview with Prince Andrew, later condemned as catastrophic, reset public opinion. The publisher notes the book as an “astonishing affirmation” of will and witness, while early major-press reviews describe it as searing and institutionally important.

As a reader, I found the voice both wounded and lucid, and the purpose unmistakably public-facing. The memoir wants to change what the law allows and what society believes.

And it does so by telling, precisely and painfully, how grooming works—and how survivors fight back.

2. Background

Before Epstein, Giuffre reports serial abuse in the home and by men with local power, a pattern that left her vulnerable to later coercion.

She recounts being “given away…as if I were a used bicycle,” and later taken into FBI custody during a raid on an abuser’s apartment, a moment that underscores how rescue rarely maps cleanly onto justice.

The memoir’s early chapters set up the psychology of control and learned helplessness, under which silence feels like safety. Horses—distance, strength, vigilance—become a recurring image for freedom imagined but deferred.

This groundwork matters: it shows why Maxwell’s polished approach at Mar-a-Lago felt like opportunity rather than risk to a sixteen-year-old. “I’d be lucky…if I could grow up to be anything like her,” Giuffre admits of that first impression.

That is grooming’s first victory—confusing care with capture.

And confusion is precisely what the book sets out to dismantle.

Inside Epstein’s houses, Giuffre describes an explicit “training period,” a daily “massage” regimen that masked abuse, and rules about silence and performance. “You want to bring a man to an orgasm, not just give him an orgasm,” she was told—an example of how sexual “instruction” becomes compliance training.

She writes of being ordered into a schoolgirl outfit, told to seem more “into it,” and bathe Epstein afterward—a script more ritual than relationship. Later she clarifies the psychological core: “the worst things…weren’t physical, but psychological,” the “forced complicity” that erodes reality testing.

Those passages are the key to understanding how children and teens can appear “autonomous” while being expertly controlled.

In short, the background is not preface; it’s causal. It explains both risk and recovery.

From here, the summary widens into the legal and public fight that defines the second half of the memoir.

3. Nobody’s Girl Summary

What the book is and what it sets out to do

Nobody’s Girl is a survivor’s memoir with a civic purpose. Giuffre recounts how early abuse primed her for Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell’s system of grooming and control, and how she later transformed survival into testimony, litigation, and policy advocacy.

The collaborator’s note is explicit: the manuscript was built to be “meticulously written” to withstand attacks from powerful people and to help other victims, not just those from the Epstein orbit. The note also details corroboration: interviews with family and a childhood friend who herself endured abuse by the same man, plus “thousands of pages of public court documents, including sworn depositions and Epstein’s flight logs,” and conversations with attorneys (Brad Edwards, Sigrid McCawley, Geoffrey Berman among others).

The book’s table of contents signals the arc—Part I “Daughter,” Part II “Prisoner,” Part III “Survivor,” Part IV “Warrior”—which mirrors the psychological journey from victimization to activism.

Part I: “Daughter”—Childhood conditions that enabled later coercion

From the outset, Giuffre situates her teenage years against a background of sexual abuse and neglect in Florida. She describes multiple abusers in and around the home, threats that enforced silence, and the way fear for a younger sibling’s safety was weaponized against her. At a therapeutic riding center founded by neighbor Ruth Menor, horses become an early refuge; helping a severely injured rescue horse named Millie gives her a language for survival even as she remains trapped at home.

The Vinceremos center and Ruth’s example—“a place that used horses to heal”—offer competence and safety that contrast with the volatility at home. Amid this, Giuffre learns how secrecy—threats like “if I ever told a soul”—keeps victims quiet, a dynamic that later maps directly onto the Epstein/Maxwell machinery.

By her mid-teens she’s working at Mar-a-Lago’s spa, finding solace in its calm and glimpsing a path into licensed massage work that could “fuel my own” healing.

That sliver of hope is shattered when, “some weeks before my seventeenth birthday,” Ghislaine Maxwell spots her outside the spa and orders the driver, Juan Alessi—“Stop, John, stop!”—before approaching the uniformed teen. The first impression—Maxwell seemed like someone to admire, even emulate—is the opening move of grooming.

Part II: “Prisoner”—How grooming worked, and how complicity was manufactured

Giuffre’s recruitment turns on promises and instruction that reframed sexual access as “massage” work.

The memoir shows the training as routine and ritual: orders about dress (e.g., schoolgirl outfits), scripted responses, and “lessons” that sexualized service under the guise of coaching—a ritual more akin to compliance drills than intimacy. (Throughout the book, she returns to how “the worst things…weren’t physical, but psychological,” a later insight she calls “forced complicity.”)

On Little St. James and during travel to places like Saint-Tropez, she narrates being “caught in the trap of familiar diminishment,” compelled to perform while suppressing rage. One vignette on a boat near St. Thomas shows a spark of resistance as she’s ordered to dance; she complies to avoid Epstein’s wrath but registers awakening anger—an interior pivot that points toward eventual flight.

A French episode underscores trafficking’s transactional logic: after intercourse, a wealthy man offers to pay “triple” if she’ll “work” for him directly—evidence that the network normalized buying access to a teenager.

The book does include famous names and settings—e.g., Naomi Campbell’s 31st birthday in Saint-Tropez, where Giuffre feels like a child among adults—but is careful about legal exposure and about centering systemic patterns over tabloidy reveal.

A key structural feature here is normalization. She is taught scripts (“be more into it”), is paid by staff after “massages,” and hears rationalizations from adults around Epstein that obscure criminality—details later echoed in depositions and court records.

The memoir’s frankness about confusion is important; as she frames it later, grooming engineered a state in which acquiescence looked like choice from the outside, which helps explain why public disbelief is so common.

Part III: “Survivor”—Leaving, loving, parenting—and the slow pivot toward speaking

Giuffre’s exit from Epstein’s orbit is less a clean break than a drift toward another life. The Australia years begin with marriage to Robbie and the birth of their children; the book is tender about motherhood (the boys’ arrivals, family rituals) while also acknowledging the lingering effects of trauma on health and mental state. (We see, for example, the long labor before her first child’s birth in 2006 and the grounded, domestic register the story adopts there.)

Her public reemergence happens in waves: Miami Herald coverage, TV documentaries, and pivotal interviews. After Epstein’s 2019 arrest and death, she stands before microphones outside court and centers survivors: “It’s not how Jeffrey died, but it’s how he lived… I will never be silenced until these people are brought to justice.” That same period includes NBC’s Dateline, a BBC interview, and Netflix’s Filthy Rich, but perhaps most formative for her sons is a 60 Minutes Australia broadcast; Giuffre chooses to let her teenage boys watch because “I want them to know what I’m fighting for.”

The memoir also recounts her own efforts to document the past. A striking scene shows her returning to Florida, knocking at the gate of former house manager Juan Alessi.

He eventually lets her in, and the conversation yields partial corroboration (he remembers recruiting day logistics; he remembers Prince Andrew in the houses) and denials (he claims never to have seen her naked). For Giuffre, the human acknowledgment—being recognized “as a person”—lands as a form of validation distinct from court filings.

Part IV: “Warrior”—Litigation, depositions, media battles, and the Prince Andrew chapter

The “warrior” phase details strategic litigation and its hostile media environment. Giuffre describes the onslaught of smear pieces—e.g., a 2015 New York Daily News front page using a leaked sealed juvenile record to imply a “false-rape” claim when she was 14; her lawyer Sigrid McCawley publicly stresses that non-prosecution does not equal falsity, explaining boilerplate decisions when evidence is deemed insufficient for trial.

We also see Maxwell’s public counteroffensive—labeling Giuffre “a liar” in January 2015 as Maxwell was revamping her public image via TerraMar. This triggers more tabloid churn and further retraumatization. McCawley’s arrival into the legal team is a turning point; Giuffre calls her presence life-changing.

When Maxwell finally sits for deposition, Giuffre includes vivid moments that illuminate defense tactics and the pressure on witnesses: Maxwell’s repeated non-answers and semantic quibbles, her outbursts (“You are trying to trap me. I will not be trapped”), and the moment she pounds the table in anger as McCawley calmly insists, “I’m in charge of the deposition.”

The book devotes a substantial section to the Prince Andrew narrative: Giuffre’s allegations, his BBC Newsnight interview (which the world judged a disaster), and the later civil settlement. The Newsnight segment is cataloged briskly—his pizza-alibi, his claim about an inability to sweat following the Falklands, and the notable absence of empathy for victims—followed by the sweeping consequences (loss of public roles; streaming dramatizations launched).

In 2022, Giuffre and Andrew reach settlement terms; the joint statement includes a “substantial donation” to her nonprofit for victims’ rights, and she agrees to a one-year gag order. Giuffre writes about waking to paparazzi outside her Australian home and choosing to protect her daughter’s birthday rather than satisfy a news cycle. Within days, another figure—modeling agent Jean-Luc Brunel—is found dead in a French prison.

The policy chapter—why statutes of limitations matter, and what changed

Late in the book, Giuffre pivots from casework to lawmaking. She argues that justice requires removing time bars that prevent trauma-delayed survivors from filing claims, and she catalogs recent progress: New York’s Child Victims Act followed by the Adult Survivors Act; Florida’s “Donna’s Law” (eliminating the statute of limitations for prosecuting offenses against minors, though without a retroactive civil look-back window); and federal updates culminating in the 2022 Eliminating Limits to Justice for Child Sex Abuse Victims Act, which removed limitations for certain federal claims brought by minor victims.

“Awareness is growing about the need for change,” she writes, and she introduces her SOAR foundation’s aims—funding prosecution, protection, and prevention, including public-education grants to help people “detect trafficking when they see it” and support victim recovery.

Her candor about health is equally important: while finishing the book she undergoes more surgery on a broken neck, struggles with mental health, and begins ketamine treatments that help “untangle my PTSD,” while accepting that recovery will remain uneven.

The book’s closing cadence—mission, costs, and the collaborator’s final note

The collaborator’s pages frame Giuffre’s final months and the push to publish. We see documentation of her explicit wish—“it is my heartfelt wish that this work be published”—even “in the event of my passing,” because the book “aims to shed light on the systemic failures” behind trafficking.

Wallace also adds context about domestic-violence allegations and family concerns that the manuscript understated long-standing abuse within the marriage; the section is careful, acknowledging competing claims, legal non-action, and posthumous family appeals for fuller context while affirming the importance of publishing Giuffre’s broader story.

The note ends on a human register—Giuffre’s last messages, her insistence on getting the book out, and the collaborator’s memory of “those last three hearts” as a symbol of the author’s instinct to “lead with love” despite “unspeakable cruelties.”

Thematic through-lines the summary preserves

1) Grooming as procedure, not melodrama. The memoir refuses sensationalism, showing how instruction (“be more into it”), uniforms, faux-employment, and adult complicity normalize abuse. The result is a chilling depiction of how teenagers can appear compliant while being controlled, and how that appearance is later weaponized to undermine credibility.

2) Forced complicity as the deepest wound. Giuffre’s later formulation—that psychological injury, the feeling of being made an agent of one’s own exploitation, can eclipse physical harm—organizes her account of flashbacks, triggers, and the long work of therapy, parenting, and purpose.

3) Systems, not just villains. While the book names people and includes high-profile episodes (e.g., Newsnight, settlement), Giuffre’s priority is the pipeline: wealth and status as shields, gatekeepers and staff as cogs, travel and housing as infrastructure, lawyers and PR as defensive membranes. That choice keeps the memoir useful as public education rather than just a scandal chronicle.

4) Evidence and corroboration. The collaborator emphasizes a defensive architecture—family interviews, a childhood friend’s testimony about shared abuse, and a trove of court documents and flight logs—precisely because discrediting survivors is a standard counter-move.

5) Advocacy as endpoint. The statutes-of-limitations chapter is not an appendix but the memoir’s aim: to ensure future Virginias are not locked out of justice by clocks they didn’t control. The launch of SOAR is the institutional version of that aim.

A few indelible scenes

Mar-a-Lago curbside recruitment. Juan Alessi remembers sweating in the car as Maxwell spotted the “notably ‘young’” teen and commanded him to stop. The tableau is small but diagnostic: status, surveillance, and selection operating in daylight.

Boat music on a black Caribbean night. A pop song blares as a handler orders her to dance; Giuffre complies outwardly while rage returns inwardly—an early crack in learned docility, preparing the ground for departure.

Knocking on Alessi’s door years later. “I’ve flown all the way from Australia to try to put together the pieces of my past,” she says; he buzzes her in. The moment highlights the value of simple acknowledgement amid pervasive denials.

Maxwell’s deposition. McCawley’s calm against stonewalling, the lawyer’s insistence—“I’m in charge of the deposition”—and Maxwell’s table-slamming loss of temper embody a shift of power, however provisional.

Before microphones after Epstein’s death. “It’s not how Jeffrey died, but it’s how he lived,” she says, redirecting attention to survivors and to enablers. The line distills the memoir’s ethic: focus on structures, not spectacle.

Prince Andrew settlement statement. The joint text acknowledges Epstein’s predation and includes a donation to victims—an institutional outcome of years of pressure, even as paparazzi crowd her family’s driveway the morning after.

The policy blueprint. The tally of reforms—NY’s CVA and Adult Survivors Act, Florida’s Donna’s Law, federal elimination of certain limitations—turns private story into public series of concrete changes.

How the book handles controversy, denial, and media dynamics

The memoir doesn’t pretend the record is uncontested. It documents Maxwell’s press attacks (calling Giuffre “a liar”), tabloid distortions (mischaracterized juvenile records), and the toxic incentive structure around “gotcha” coverage.

It also records careful self-limits. Giuffre acknowledges that as “a parent” she will not publish certain names at certain times, prioritizing family safety over public appetite. The book’s strength lies in describing the architecture of exploitation and the pathway to justice rather than serving as a catalog of fresh allegations.

Even allies and institutions are shown with nuance. The Newsnight chapter—Andrew’s insistence on honor, his pizza and non-sweating claims—reads not as triumphalism but as a portrait of how public relations can backfire when empathy is absent. The aftermath (loss of roles, projects dramatizing the fiasco) turns a single interview into a cultural hinge that widened space for survivors to be believed.

Final chapters: exhaustion, persistence, and legacy

The last pages braid victory and cost. On one side: legal milestones, policy changes, SOAR’s mission, and a growing consensus that time bars must go. On the other: surgeries for a broken neck, setbacks in mental health, and candid documentation of treatments like ketamine for PTSD. “Sometimes I will simply not be okay,” she writes, refusing the myth of linear healing.

The collaborator’s epilogue is painful and clear. It recounts Giuffre’s explicit written instruction—emailed April 1—that the book “be published” because it addresses “systemic failures,” even “in the event of my passing.” Wallace also records family concerns that the manuscript underplayed domestic abuse and includes limited earlier police interactions without charges, presenting the complexity rather than black-and-white closure.

The final note returns to the reason the book exists at all: to “inspire more people to fight” for change, especially eliminating statutes of limitations for child-sexual-abuse crimes.

What you take away

A precise map of grooming and coercion.

- Recruitment at a workplace, praise and aspiration (Maxwell’s polished persona), learned scripts around “massage,” and adult complicity that makes trafficking look like employment. (See the Mar-a-Lago approach and Alessi’s recollections.)

The long tail of trauma.

- Even with family and global advocacy, aftermath includes surgeries, chronic pain, and PTSD care—work that continues beyond headlines.

Evidence under fire.

- The manuscript is built on interviews, court filings, and logs, anticipating denial and defamation; readers get process, not just claims.

Public narrative turning points.

- From courthouse steps (“It’s not how Jeffrey died…”) to

Newsnight

- , the book charts how public opinion shifted and how that impacted institutions, including a royal household.

Concrete reforms.

- New York’s CVA/ASA, Florida’s Donna’s Law, and federal eliminations of certain time limits; plus SOAR’s three-part focus (prosecution, protection, prevention).

Measured restraint.

- The memoir refuses to inflate or sensationalize; it privileges systems, survivor solidarity, and policy over gossip—consistent with its mission. (Her declaration as a parent comes first when deciding what to publish now vs. later.)

This memoir is less a dossier and more a manual—showing, step by step, how grooming corroded choice; how escape, love, and parenting reclaimed life; how law and media can be weaponized and re-weaponized; and how reform becomes the real ending. By the time you finish this summary, you’ve met each pillar of the book: the childhood crucible; the Epstein/Maxwell system; the public and legal reckoning (including Prince Andrew); and the policy blueprint Giuffre hoped would outlive her.

3 Nobody’s Girl Analysis

Does the author substantiate her claims?—yes, through internal documentation and external records, then by situating her story in a measured policy agenda.

First, the memoired scenes of grooming are narratively persuasive and sociologically accurate: they do not rely on shock, but on procedure—how praise, gifts, and “training” create compliance and blur consent.

Second, the collaborator’s note details exactly how memories were checked—family interviews, a professional fact-checker, and side-channel sources (press interviews, other books, legal transcripts).

Third, the macro data on online exploitation spikes and the historical record of Epstein’s prosecution era serve as independent anchors.

Does the book fulfill its purpose?—largely, yes: it educates on grooming mechanics, foregrounds survivor solidarity, and explains why statute windows matter for trauma-delayed disclosure.

It also chooses restraint where tabloids wouldn’t: the focus is on systems and recovery, not on feeding a celebrity-scandal appetite.

That editorial ethic serves the book’s credibility and long-tail impact.

Where the memoir particularly excels is in translating psychological injury into civic language: “forced complicity” as the most destructive wound is a clinical-adjacent observation wrapped in clear prose.

Her courtroom and legislative updates are plain-English, useful for readers new to the terrain; the descriptions of bail hearings and asset disclosures demystify the scale of power at stake. Giuffre’s through-line—I am a parent first; I will not endanger my family—adds a moral center that complicates the demand some readers have for “new names now.” As a piece of public pedagogy, Nobody’s Girl rings like a bell: it teaches detection, insists on timing that respects trauma, and centralizes survivor coalitions.

Finally, by acknowledging ongoing mental-health treatment and imperfect peace, Giuffre inoculates the book against “happy ending” myths—recovery is real and unfinished.

In academic terms, this is the rare memoir that doubles as praxis. In civic terms, it’s a teach-in.

And that, I think, is why it will outlast the news cycle.

4. Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths: corroboration, clarity about grooming, refusal to sensationalize, concrete policy levers, survivor-to-survivor voice.

The strongest sections translate daily rituals of control into the reader’s body—outfits, scripts, orders—showing how exploitation hides in plain sight. I admired the legislative literacy: readers leave knowing what the Child Victims Act and Adult Survivors Act did and why “look-back windows” matter. The presence of SOAR and the resource list signal that testimony isn’t the endpoint—there’s a next action.

Weaknesses: the necessary legal caution around naming can frustrate readers seeking new disclosures, and some digressions on media miscoverage may feel repetitive if you followed the case closely.

Yet those choices protect the book’s purpose and the author’s family.

Personally, the passages on “forced complicity” and the parental frame cut the deepest.

They translate theory into felt reality.

I’ll add that the middle chapters on marriage and spirituality keep the memoir from becoming solely a case file; they remind us that survivors are not only what was done to them but also what they build afterward. The writing isn’t “literary” for its own sake; its clarity serves comprehension and advocacy.

At times I wanted more about institutional mechanics (banks, foundations, gatekeepers) around Epstein’s funding streams, but that may be a different book’s remit. The trade-off is that this one stays readable and teachable—ideal for book clubs, classrooms, and trainings. On balance, the memoir achieves what it promises: testimony that moves policy.

Even as a seasoned reader of abuse narratives, I learned new language for old injuries. That’s a gift—and a tool.

And it’s the tool survivors asked for.

5. Nobody’s Girl Reception, criticism

Early mainstream reviews call Nobody’s Girl “searing” and institutionally significant, highlighting its refusal to sensationalize while documenting systems and enablers.

Coverage also frames the book inside the year’s royalty-and-Epstein headlines, including renewed attention to the 2019 BBC interview widely judged catastrophic for Prince Andrew, a chapter refreshed in recent commentary.

Publishing reports confirm the memoir’s posthumous status (completed with Wallace) and the U.S./UK releases (Knopf/Penguin). As a corrective to the rumor mill, the book’s collaborator emphasizes evidence standards; that meta-narrative influences how future survivor memoirs may be fact-checked and framed.

In my view, two influences will linger: public literacy about grooming, and policy momentum on statutes of limitations and victim services. Those are outcomes beyond book pages.

And they’re exactly what Giuffre wanted.

6. Comparison with similar works

If you read Julie K. Brown’s Perversion of Justice (journalism) and Geoffrey Berman’s Holding the Line (prosecutorial view), Nobody’s Girl adds the survivor’s interior and legislative vision.

Brown’s reporting resurrected attention and mapped institutional failures; Giuffre’s memoir humanizes those failures’ daily cost while clarifying grooming and policy. On feminist frameworks for trafficking, academic and policy texts analyze structures; Giuffre makes those structures visceral and visible. In short, where investigative books marshal documents, Nobody’s Girl turns documents into consequences you can feel.

Readers seeking more on trafficking’s global dimensions could pair this with human-rights reading lists and survivor-led abolitionist work.

But start here, because the lesson begins in the body and ends in law.

That arc is this memoir’s unique value.

And it’s why this book will be taught.

Finally, when readers revisit the 2019 BBC interview and its aftermath, they’ll see how media moments can become catalysts for public opinion and policy. This memoir captures the human cost behind those clips.

Which is what we too easily forget.

7. Conclusion

I recommend Nobody’s Girl to general readers, students, clinicians, journalists, and policymakers who need a survivor-centered, evidence-checked map of how grooming and justice actually work.

For general audiences, the prose is direct and humane; for specialists, the policy scaffolding and citations serve as entry points for reform.

Book clubs should include a content-note, then use the SOAR resources page and local hotline info to connect story to action.

If you can handle the subject matter, you will leave not only informed but reoriented.

Because this is not just Virginia Roberts Giuffre’s story; it’s a field manual for recognizing predation and insisting on change.

And it does what the best memoirs do: transform private pain into public good.

I believe its influence will be measured in lawsuits filed, windows reopened, and survivors who finally feel less alone.

News

Okurrr! Cardi B reacts hilariously to fan caricature, sending social media into a laughing frenzy

Cardi B, the rapper known for her bold statements and vibrant personality, recently made waves with an unexpectedly funny moment…

SH0CK! Rapper THF Bay Zoo in critical condition after a bl**dy South Side sh**ting — the entire neighborhood shaken as 39 sh3ll casings littered the scene

The Chicago rap community was shaken after reports emerged that THF Bay Zoo — real name Devonshe Collier, a longtime…

Virginia Giuffre wrote in her memoir “Nobody’s Girl”: “I tried to believe Jeffrey Epstein wasn’t a monst3r — because the truth was too horrifying

A posthumous memoir by Jeffrey Epstein accuser Virginia Roberts Giuffre offers an expanded account but few new revelations about her longstanding claims…

Cardi B Sh0cks Fans — Divorce From Offset Won’t Stop Me From Marrying Again in the Future

Cardi B recently shared that her divorce from rapper Offset has not deterred her from wanting to get married again…

Breaking: OTF Rapper THF Bayzoo Reportedly Sh0t Multiple Times in South Side Chicago

Chicago is in shock as THF Bayzoo, an OTF rapper and close associate of Lil Durk and King Von, was…

No Limit vs Cash Money Verzuz Review: Hits, Nostalgia, Who Won in Vegas

The label showdown at ComplexCon in Las Vegas on Oct. 25 brought together two New Orleans rap dynasties and offered…

End of content

No more pages to load