📰 The Vile Truth Behind “Roofman”: Why Hollywood’s Latest True Crime Drama Is Stirring Outrage

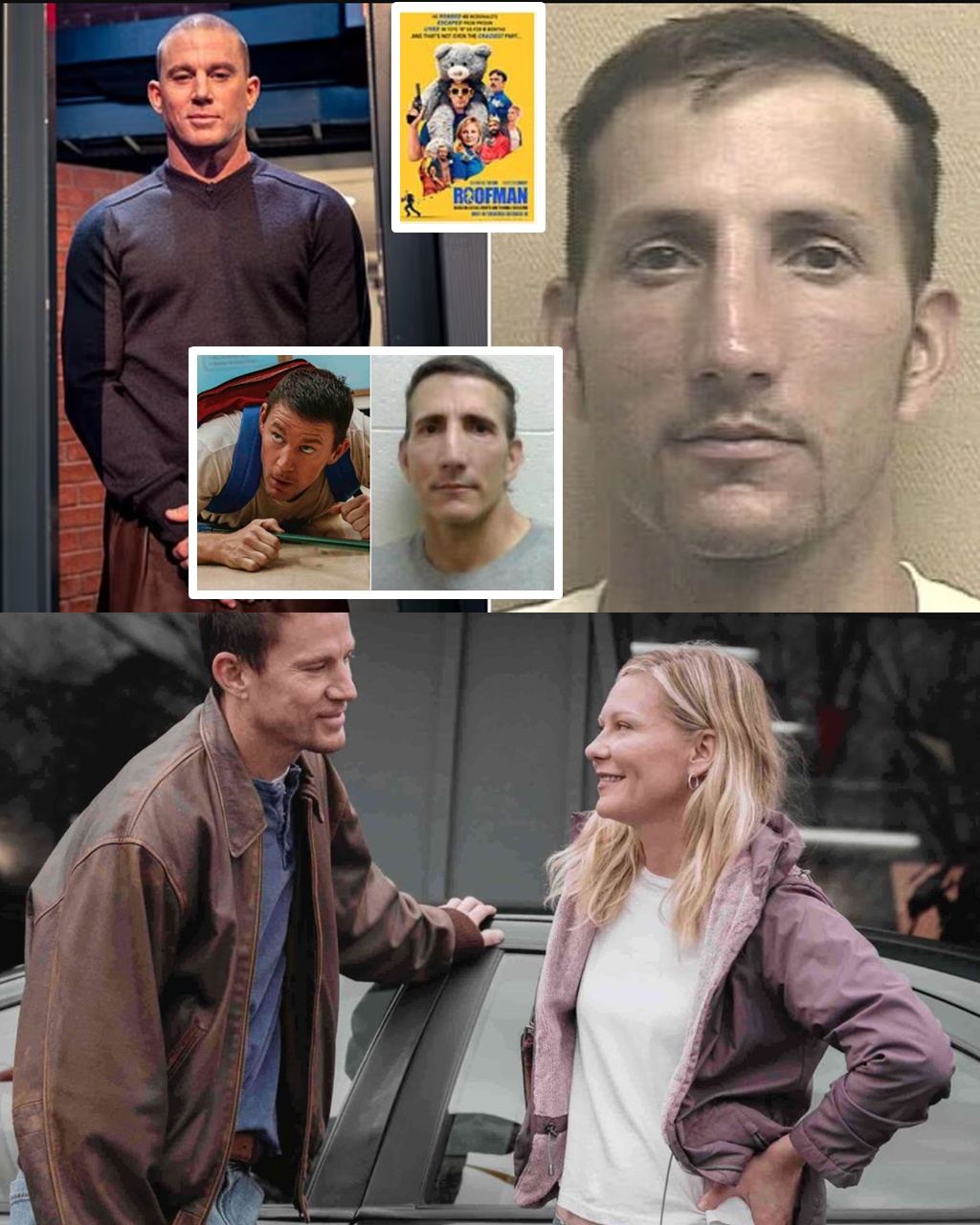

When Roofman, directed by Derek Cianfrance and starring Channing Tatum, was announced, it immediately caught attention — not only because of its star-studded cast but because of its source material: the real-life story of Jeffrey “Roofman” Manchester, a convicted burglar who turned his crimes into an eerie kind of legend.

The film, marketed as a “human story of survival and redemption,” has reignited a heated debate: When does empathy become glorification? And is Hollywood once again turning a sociopath into a sympathetic icon?

1. The Real Story Behind “Roofman”

Jeffrey Manchester wasn’t a misunderstood drifter — he was a career criminal.

A former Army serviceman, Manchester committed a string of daring burglaries across the United States in the late 1990s and early 2000s, famously breaking into McDonald’s and other fast-food chains through the roof, earning him the nickname “Roofman.”

He was finally caught in 2000 and sentenced to 45 years in prison. But four years later, in a move that could have come straight from a movie script, he escaped from a North Carolina prison and hid for months inside a Toys “R” Us store, sleeping among bicycles and Nerf guns.

During that time, he befriended a local woman named Leigh Wainscott — who had no idea she was dating a fugitive.

2. What the Film Gets Right

To its credit, Roofman explores the loneliness and desperation of a man trying — and failing — to reintegrate into society. Derek Cianfrance, known for emotionally raw dramas like The Place Beyond the Pines, focuses less on the crimes themselves and more on the psychological decay of isolation, the yearning for connection, and the illusions of redemption.

Channing Tatum’s subdued performance paints Manchester as haunted, fragile, and painfully human. Critics have praised this choice for bringing emotional depth to a character who could easily have been played as a cartoonish villain.

3. The Problem: The “Hero Treatment” of a Criminal

But this emotional framing is also what’s drawing sharp criticism.

The real Manchester wasn’t a misunderstood philosopher — he was a manipulative and compulsive offender who terrorized employees and repeatedly violated parole. The film’s decision to romanticize his actions — portraying him as a lost soul instead of a predator — risks sending the wrong message entirely.

By highlighting his charm, his supposed “gentle side,” and his connection with Leigh, Roofman softens the severity of his crimes. In doing so, Hollywood blurs the moral line between fascination and forgiveness.

“We keep calling these films ‘based on a true story,’ but what we’re really watching is a curated empathy experiment,” one critic noted. “We’re not learning about criminals — we’re learning how far Hollywood will go to make us pity them.”

4. Fact vs. Fiction — and the Scenes Hollywood Cut

Ironically, some of Manchester’s most unbelievable real-life actions were deemed “too bizarre” for the movie.

For example:

He once disguised himself as a rabbit during a church Easter event.

He snuck into police stations and public spaces to steal supplies.

His elaborate escape and months-long deception were so absurd that some producers thought audiences wouldn’t believe it was true.

By cutting these outlandish, unsettling details, the film paints a neater, cleaner image of a man who was far more manipulative — and far less sympathetic — in reality.

5. The Ethical Dilemma: Who Gets to Tell This Story?

Reports suggest Manchester himself was consulted during production. While that’s not unusual for biographical films, it raises questions:

Is it ethical to allow a convicted criminal to influence how his story is told — especially when victims are still alive and affected?

Hollywood often justifies this approach as “giving both sides of the story.” But when the “other side” is a sociopath seeking to rebrand himself, empathy can become exploitation.

6. Why Viewers Keep Falling for It

There’s a reason audiences are drawn to characters like Roofman.

They reflect something universally human: the desire to be forgiven, the fantasy of starting over, the illusion that people can change — even when they can’t.

But movies like this can turn real pain into moral spectacle — where crimes are washed away in a haze of sadness, slow music, and soulful eyes. It’s not just storytelling. It’s seduction.

7. The Bigger Question: When Does “True Crime” Become “False Comfort”?

Roofman forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth:

Hollywood isn’t always interested in what happened — it’s interested in how audiences feel about what happened.

By packaging sociopathy as sensitivity, the industry risks teaching viewers that all criminals are victims, and that every act of evil just needs a backstory to be forgiven.

🎭 In the End

Roofman is stylish, emotionally rich, and beautifully acted.

But beneath the artistry lies something deeply unsettling: a rebranding of guilt.

Jeffrey Manchester wasn’t a folk hero. He was a burglar who violated trust and manipulated kindness. And no matter how many slow-motion montages or sad piano tracks you layer on top, that truth shouldn’t be rewritten for the sake of cinematic comfort.

So when you walk out of the theater feeling “moved” by Roofman’s tragedy — remember whose story it really is.

News

Rylan’s Breaking Point: After Years of Smiles, He Explodes Over Backlash — And Threatens to Expose What He Says Must Be Brought Down

When a public figure decides to abandon the polished façade, often what emerges is far more raw and revealing than…

When the Woman You Love Becomes a Stranger: Martin Frizell Speaks Out As Alzheimer’s Steals Fiona Phillips — His Heartbreaking Admission Hits Hard

Every word from Martin Frizell seems to carry the weight of a world he never expected to live in. He…

From Candy on the Corner to Commanding the Cosmos: How Elon Musk’s Childhood Hustle Became the Fuel for a Trillion-Dollar Empire

The story begins not in a boardroom, but on a dusty street corner — where a young boy handed out…

From Billion-Dollar Mansions to a $50,000 Tiny Home: Why Elon Musk Traded Luxury for a Life Measured in Square Feet, Not Status

At first glance, it sounds like satire: the world’s richest man — worth over $333 billion — living in a…

She Raised the World’s Richest Man — But Her Own Story Is Even More Extraordinary: 5 Things You Never Knew About Maye Musk

On her birthday, Maye Musk wrote a social media post thanking Elon Musk for sending her ‘beautiful flowers’. Here’s some…

‘He’s Not Just a Billionaire, He’s My Son’: Elon Musk’s Mother Shares Emotional Message About the Man Behind SpaceX, Tesla, and a Lifetime of Genius

Elon Musk’s mother, Maye Musk, sets the record straight regarding her son’s social media activity. The author and veteran model,…

End of content

No more pages to load