As the lightly-armoured Willys jeep crawled through a remote village deep in the Yugoslavian mountains, the two British soldiers riding in her instantly sensed that something wasn’t quite right.

At the wheel was ‘Blondie’ Smith of the Long Range Desert Group – that band of reconnaissance specialists who, until recently, had supported the SAS in the North African desert.

Now it was Christmas in 1943, and they were operating deep in war-torn Yugoslavia.

Beside him sat his good friend John Gomer Morris, of the recently formed Raiding Support Regiment (RSR) – a unit set up to provide heavy weapons support to special forces operating deep behind the lines.

Morris cradled a Tommy gun with a drum magazine in his lap like a 1920s Chicago gangster.

The pair had been sent to collect the Christmas mail from Allied-held Dubrovnik.

But after drinking more than their fair share of raki, a potent aniseed-flavoured local spirit, they were full of more than a little festive cheer, and so their return journey had become something of a blur.

‘We lost our way coming back,’ Morris, now aged 103 and a Chelsea Pensioner, recalls.

By the time they realised their error, they found they were driving through a German-held village.

+8

View gallery

Chelsea Pensioner John Gomer Morris pictured at the National Army Museum last month. He attended the launch of the book SAS The Great Train Raid, by historian Damien Lewis

+8

View gallery

John Gomer Morris in 1946, after his war service. The 103-year-old served in the elite Raiding Support Regiment

Considering just which way to turn, luck was not on their side. Ahead of the speeding jeep appeared a group of German soldiers, who seemed just as stunned to see a British vehicle as Morris and Smith were to see them.

But it was the season of goodwill to all men, so they decided to offer a rare moment of mercy after months of raiding operations deep behind the lines.

‘Fire over their heads,’ Smith hissed to Morris. ‘Don’t shoot anybody. It’s Christmas Eve. Just frighten the life out of them.’

Seeing sense in his friend’s counsel, Morris raised his Tommy gun and fired a burst just over the top of the throng of stunned German troops.

As the they dived for cover, Smith stamped hard on the accelerator, spinning the steering wheel as he executed a screaming about turn.

As the pair of inebriated elite forces soldiers sped away, they let out a sigh of relief, for no enemy fire chased after them, and they could hear no vehicles in pursuit.

Clearly, the Germans had as little appetite for battle or bloodshed as the two British raiders.

John Gomer Morris is now the oldest resident of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

His remarkable age and sharp memory have made him something of a celebrity both inside the famous institution and beyond its walls.

He frequently visits local schools to teach the younger generation about the Second World War, keeping history alive in a way no textbook can.

+8

View gallery

John Gomer Morris with historian Damien Lewis at the launch of his book SAS The Great Train Raid at the National Army Museum in October

But what makes Morris truly unique is that he is the last surviving member of the RSR, which is one of the war’s least known special forces units.

Born in the Cotswolds in 1922, Morris moved to Kent at the age of five with his older brother, Alan.

He remembers his father as a troubled man. ‘He was a Royal Engineer, a sapper, during the First World War, serving on the Western Front in the trenches of the Somme, Ypres and Passchendaele.’

Morris believes the horrors his father endured fuelled his heavy drinking in later life. ‘It wasn’t a very nice war to fight,’ he adds in typically understated fashion.

In 1938, Morris joined the 89th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, a Territorial Army unit in Kent.

Eighteen months later, he was manning anti-aircraft guns in London during the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. ‘Our job was to break the bombers up so the fighters could get at them.’

But not every shell hit its intended target. One day, while firing at a Dornier reconnaissance plane, Morris’s aim was slightly off.

‘We had three-inch guns. They weren’t very good, with an open sight. I fired at the Dornier and missed.’

+8

View gallery

Yugoslavian women partisan fighters shoot at practice targets while resting at an Allied camp in Italy

Instead, his shell hit the chimney of a nearby oast house, sending it crashing to the ground. ‘I wasn’t very popular after that,’ Morris says with a small shrug.

By 1943, he was old enough to serve abroad, and was sent to Algeria as a machine-gunner and trained radio operator.

It was there that he fell ill after drinking water poisoned by the enemy. While recovering, Morris came across an opportunity that would change the course of his war.

The army was seeking volunteers for a new special forces unit being raised by Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Thomas Devitt, who pre-war had played rugby for England.

Its name was literal: the Raiding Support Regiment, created to provide supporting firepower – anti-aircraft, anti-tank, mortars, machine guns, and mountain artillery – to units such as the SAS and the Long Range Desert Group.

They would operate across Yugoslavia, the Adriatic islands, Greece, and alongside the Yugoslav partisans in the mountains of Bosnia, Croatia, and Albania.

For Morris, it was exactly the kind of challenge he hungered for. ‘I always wanted to go in the special forces.

‘When you’re young you want adventure. It’s a different state of mind. You don’t think you’re going to get killed anyway.

‘I should have been a few times, but the Lord in his wisdom looked after me….’ Almost as an afterthought, he adds of the Germans, ‘They weren’t very friendly, you know.’

Morris was accepted into the RSR – motto: Quit You Like Men – and was dispatched to Palestine for specialist training.

+8

View gallery

Yugoslavian partisan fighters pictured in January 1943

There he learned small boat handling, mule management for mountain operations, and weapons skills. He also completed rigorous fitness training.

The final stage was the parachute school at Ramat David, in what is now Israel.

He remembers his first parachute jump vividly. ‘It was bloody awful. I was pushed out, through the bomb doors of a Wellington bomber.

There were five of us in a stick. We used to do our training jumping out of the back of a lorry travelling at 30 mph. We had one chute as well, no reserve.’

The RSR’s headquarters was a convent near Bari, Italy, with one section based on the partisan-held island of Vis in the Adriatic Sea.

Soon enough, Morris found himself deep in the hills of Yugoslavia on a special mission of his own.

Not attached to any of the RSR’s five batteries – ‘I was a floater’ – he had become an expert radio operator and was sent directly to the headquarters of the partisan leader Josip Broz Tito.

‘My job was teaching the partisan girls how to improve their morse code and how to use the radio sets (provided by the British). They were very beautiful girls. We all slept in one big log cabin.

‘This beautiful girl was sleeping next to me… they used to go to bed with hand grenades around their waists.’

Morris was deeply impressed by the partisans – especially the female fighters. ‘They used to go out and come back, some of them shot up. They used to fight like men.’

+8

View gallery

Josep Broz Tito was the leader of the partisans in the war. He went on rule his country as a Communist

Not only were they fighting the Germans, they were also hunted by the Ustaše, the fascist Croatian militia and Nazi collaborators. ‘They were bastards, worse than the German SS,’ Morris recalls.

Life in the Yugoslav mountains required improvisation and endurance. Morris spent countless days hauling equipment over rugged terrain, usually by mule – the only reliable transport in that unforgiving landscape. But the animals had a mind of their own. He remembers one particular incident:

‘We couldn’t get the mule up the mountain. It got so far then the Germans decided… not being appreciative of us, to send some shells over. The mule just wouldn’t move, so we tied it to a tree and carried the wireless on our backs up to where we were supposed to be, and left the mule there.

‘When we got back in the morning the mule was gone. We never saw it again.’

As Morris was coaxing stubborn mules through the hills of Yugoslavia, his brother warriors were taking part in missions every bit as hair-raising.

All along the Adriatic coast, the men of the RSR were striking at the Germans wherever they could – launching audacious raids on occupied islands, ambushing enemy patrols, and even seizing enemy supply vessels under cover of darkness.

One such effort, Operation Floxo, in October and November 1944, set out to slow the German withdrawal as their forces streamed north, terrified of being trapped by the advancing Red Army.

For weeks the RSR poured artillery and mortar fire in support of British Commandos and their Yugoslav comrades.

The combined pressure forced the Germans onto a longer, far more treacherous route, where they were harried relentlessly by Allied and partisan fighters.

Yet even as the tide turned, politics intervened. By the winter of 1944 and early 1945, with the Germans driven from Yugoslav soil, British involvement came to an abrupt halt.

Tito, by now leaning firmly towards Stalin, ordered all Allied personnel out of the country.

After months of shared danger, it was a sudden and sour ending to an extraordinary partnership.

By then, Morris’s war was already over. Dispatched to a hill-top Yugoslav position to radio back ‘fire orders’ – the coordinates and location of enemy positions – Morris and his one RSR comrade were ambushed by the enemy.

Taken prisoner, they were held in a concrete blockhouse. Luckily, his mate had a pistol cunningly concealed in a water bottle.

They managed to unsolder the bottle, and at gunpoint tied up their guard, before making their getaway on foot.

Back safely in Allied lines, Morris fell ill with a bout of malaria, no doubt picked up in North Africa.

He was hospitalised when the RSR deployed into Greece to harass the retreating German forces.

‘A lot of my friends got killed in Greece,’ Morris reflects. He felt guilty not to be there fighting alongside them.

At the end of the war, John found himself guarding German prisoners on the Adriatic coast near Bari.

The men he encountered were not the arrogant Nazi ideologues many imagined.

‘They hated Hitler,’ he recalls. ‘I sat there playing cards with them, and I started winning all their money. But they were very good blokes. They were very anti-Hitler.’

Demobilised in 1946, John returned to civilian life – but his adventures were far from over.

In December 1963, he and his family boarded the cruise ship TSMS Lakonia for a holiday to the Canary Islands.

Late on the night of 22 December, a catastrophic fire broke out and the order was given to abandon ship.

John got his wife and children into one lifeboat and helped his mother-in-law into another before leaping into the cold Atlantic himself, clinging to a floating piece of deck cargo alongside another passenger.

For six hours they stayed alive in the freezing water before being rescued.

+8

View gallery

John Gomer Morris was on the cruise ship the TSMS Lakonia when a fire broke out on the night of December 22, 1963

+8

View gallery

The Daily Mail’s coverage of the fire that broke out on cruise ship the TSMS Lakonia, which John Gomer Morris was on with his family

Only then did he learn that his mother-in-law had died. Her lifeboat davits had snapped during lowering, throwing the passengers into the sea.

She was one of 128 people who lost their lives. Her body was never recovered.

John later emigrated to Australia, settling in Parramatta, Sydney, to be closer to his daughter. He remained there for almost 40 years.

In 2020, with assistance from the charity Pilgrim Bandits, he returned to Britain and was granted a place at the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Today, at 103, he spends his time promoting the hospital and speaking to schoolchildren about his wartime experiences and his life in special forces.

Looking back on more than a century of conflict, survival, and change, John is reflective about the modern world.

‘People are putting greed before need,’ he said. If we tried to save people rather than kill them, the world would be a better place.’

It’s difficult to disagree with him.

SAS The Great Train Raid: The Most Daring SAS Mission of WWII, by Damien Lewis, is published by Quercus and available from the Mail bookshop.

News

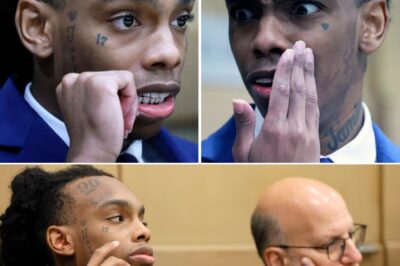

WE WERE NOT READY… YNW MELLY ESCAPES ALL CHARGES AT THE VERY LAST MINUTE! ⚖️ America Stunned as Prosecutors Pull Back Just 24 Hours Before a Life-or-De-ath Trial — Miracle or the Silence Before a D-e-a-dly 2027 Storm?

America woke up in disbelief. With just 24 hours left before one of the most explosive trials in modern music…

WE COULD NOT HOLD BACK OUR EMOTIONS… AS D-E-A-TH LOOMS CLOSER ON THE RAPPER! 💔 • Fans Pray as YNW Melly’s Charges Drop Sparks Fragile Hope Before 2027 Trial That Could Bring the Harshest Sentence in Music History

Even as millions of fans across the globe pour out prayers and messages of unwavering support, a chilling shadow continues…

They Were His Reason to Live… But He Still Doesn’t Know They’re Gone: Inside the Bruce Highway Crash That Turned a Family’s Hope Into Silence!

A Queensland family has been left “shattered” after the shock deaths of a young mother and daughter in a crash that also…

EXCLUSIVE: ‘I Had No Idea’: Junior Andre Breaks His Silence After Mum Katie Price’s Sh0ck Wedding — and Makes a Candid Romance Admission That’s Turning Heads

View 6 Images Junior Andre has spoken out(Image: Ken McKay/ITV/Shutterstock) Whilst Katie Price has walked down the aisle in a quickie…

A Dream Holiday Turns Into a Nightma:re: British Couple D-i-e Just Days Apart After What Was Meant to Be the Trip of a Lifetime…

Malcolm Richmond, 71, and his wife Elaine, 70, died during a Christmas holiday to the Maldives before it ended tragically…

Trapped Between Life and De-ath: Father Fights for Survival, Unaware His Wife and Daughter D-i-e-d in Bruce Highway Trag:edy

A grandmother is facing unimaginable heartbreak after losing both her daughter and granddaughter at the same time in a devastating…

End of content

No more pages to load